A History of Kenfig

Kenfig Heritage – History (Kenfig/Margam/Glamorgan) – The Vale of Glamorgan (Bridgend History)

Book Review:

Bridgend, The Story of a Market Town by Henry John Randall (1956/57)

This book sets out “to portray from exasperatingly inadequate materials the origin & growth of a local community.”

The community is Bridgend and the author, Mr H.J. Randall, well known both as an archaeologist & as a general historian, is a member of a family which has played a prominent part in the affairs of Bridgend for over a century & a quarter – he brings to his task therefore, the double advantage of being both a native of the town and also an accomplished scholar.

His work is to be welcomed, not only because Wales’s contribution to this form of historical writing has hitherto been for the most part far from distinguished, but also because this book is a model of how a town history should be written.

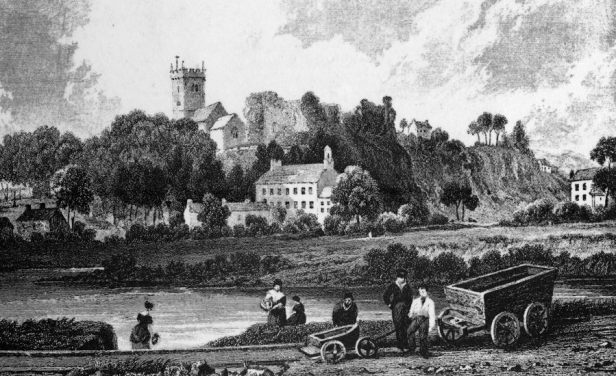

The name Bridgend was originally applied to the small urban centre which grew up at the eastern end of a bridge built over the river Ogmore in the early 15th century.

The site was a good one, well drained & the centre of a network of communications stretching in all directions except that of the sea, for, alone among the rivers of South Wales, the Ogmore has never been navigable.

Photo courtesy: Hellohistoria

In due course the town was to grow upwards from the valley floor to absorb the two earlier settlements on the hills above – Newcastle, a Norman creation, on the west of the river & Nolton, a hamlet known to have been in existence by the end of the 12th century, on the east.

But this process of absorption was long hindered by the presence of the river & until the 19th century the area came under two quite separate parochial governments, Newcastle & Coity Lower.

Bridgend never became a borough but grew up as a small & undifferentiated area within the manor of Coity Anglia which was part of the lordship of Coity.

The 15th century settlement seems soon to have become one of the busiest trading centres in the county with two annual fairs & a weekly market, the tolls of the latter being valued in a manorial survey of 1631 at the considerable sum of £20 per annum – unfortunately the town was not on the main road & early references to it are consequently few and rather desultory.

Leland seems to have been unable to decide whether it should be described as a village or as a market town.

Rice Merrick in 1578 listed it, rather enigmatically, among the “Seven Dangerous places sometime in Glamorgan.”

More favourable was an 18th century visitor, John Wesley, who reports having encountered at Bridgend both “the fear of God” and “the heaviest rain I ever remember to have seen in Europe.”

At the beginning of the 19th century Bridgend was still very small with a population of under a 1000 people, still primarily a market town, but with shoe making & quarrying among its other occupations – in the previous decade a large & ambitious woollen factory had been erected but it had collapsed by 1820 owing to the high cost of production, attributed by Mr Randall to defective management.

Yet it was now that the change was to come, for between 1820 & 1855 the modern town was created.

Photo courtesy: Francis Frith

The main South Wales road was diverted to run through Bridgend & a new bridge was built – the railways arrived, beginning with a tramway and ending in 1851 with the main South Wales line.

To these new communications were added gas works, a water supply, a new market, a new town hall (owned, oddly enough, not by the town, but by charitable trustees), schools, banking facilities, a new church & several additions to the existing number of Nonconformist chapels.

The cholera epidemic of the late 1840s led to the admirable survey of the town, conducted by the antiquary G.T. Clark & it was on his recommendations that the administrative integration of the whole area was first achieved by the creation of the local Board of Health in 1851.

The cultural needs of the town in the meanwhile must have been more than satisfied by the Bridgend Mechanics’ Institute (1848) which aimed, so the president remarked at its first anniversary meeting, at placing “the aproned artisans of Gwalia on a level with Greece or Rome’s greatest philosophers.”

Bridgend was now a prosperous small town & this state of affairs remains unchanged today, despite such recent developments as the arrival of the headquarters of the Glamorgan Police and during the last war, of a large Ordnance factory employing 40,000 workers, now converted into a trading estate.

In Mr Randall’s words, “the main story is one of continuous, but unspectacular development.”

This story the author tells simply & sensibly and the book contains little to which one might take exception.

Considerable problems of arrangement are involved in writing a book of this nature, for in this, more than in most kinds of history, the extent of the treatment given to any particular part of the whole story depends less on its relative importance than on the quantity of evidence available.

Mr Randall gives each topic a chapter to itself and the succession of short chapters, sometimes only a page or so in length, produces a jerky, rather scrappy effect.

There is a good index & there are some maps but the book badly lacks a street plan of the town and a modern air photograph would have been instructive – we are told little about Bridgend’s inhabitants, their origins or their language and there is nothing at all about the houses in which they lived.

There are rather a large number of misprints & one or two actual errors.

It has, for example, long ceased to be true to say (p.3) that at Aberthaw “little coasters still arive and depart”; few modern historians would agree with the statement (p.8) that the Norman kings could not afford to employ mercenary troops and it is disconcerting to be told (p,64) with reference to an allegedly corrupt Deputy Sheriff of 1738, that “in courtesy to the dead I have not troubled to ascertain the identity of this suspected official.”

But these are minor blemishes on what is in most respects an admirable piece of work, well documented & written in a lucid and intelligent manner.

Mr Randall skilfully avoids the two main pitfalls which beset the local historian: mere quaintness on the one hand and mere illustration on national history on the other.

The book contains little that is new to the general historian (although facts about Bridgend’s prosperity during the 1840s are interesting) but this is because it is an example of the best kind of local history – that written for its own sake & needing no justification outside its own terms of reference.

The author brings to his work both erudition and local patriotism, but he has no special advantages as far as his evidence is concerned – materials equal or superior to those which he uses to sich effect for Bridgend exist for almost every other town in Wales.

It is to be hoped that this excellent book will stir others to similar endeavours.

Original works: K.V. Thomas, All Souls College, Oxford, 1956, 1957.

website researcher/author: Copyright © Rob Bowen, Kenfig.org Local Community Group, 2019 Source: Transactions of the Honourable Society of Cymmrodorion, 1956, 1957 (Reviews) – p.136-137; Welsh Journals Online (National Library of Wales – https://journals.library.wales/home);